Wood is the essential material that makes violin making possible. Living here in the Vermont countryside, there is an abundance of interesting wood growing all around me. In my fifty years of violin making, I have experimented with very different kinds of wood. When I choose one wood over another, I explore how that difference changes the making process and how that particular wood expresses itself in the finished instrument.

Most violin makers today purchase their materials from a wood dealer who specializes in types of wood known to work well within the traditional practices of violin making. But rather than having one way of working, then selecting the wood that works with that method, I prefer working with a wide range of wood. I enjoy the challenge of understanding how to make violins in a more flexible way in order to fit the characteristics of a particular piece of wood.

I’ve explored the extremes. I’ve built fiddles out of hard maple, which is very heavy and dense, and violas out of willow and poplar that are very light. If I absolutely had to limit myself, I would probably go back to the core of violin woods that are traditionally used. But I think that my understanding of the violin has definitely improved through working with a wide variety of woods, and I believe this breadth of experience makes what I do with a standard piece of wood better than it would be otherwise.

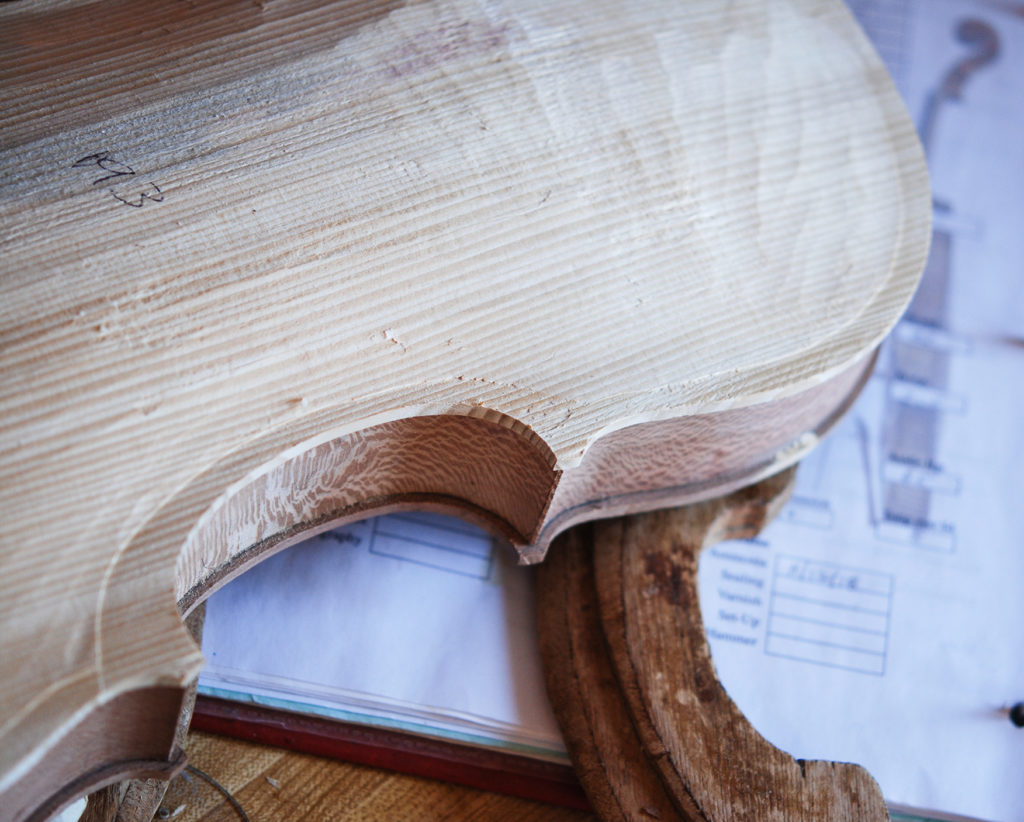

I like the idea of making things that are (literally) rooted in the community and the place where they are made. A friend of mine, Greg Moschetti, was having some stand improvement logging done on his woodlot a mile from my home, and I arranged to have a load of firewood logs delivered to heat my home and shop. One log just happened to be a gorgeous silver maple with wonderful curl in it, nice and clean. A week’s work converted that log into wood that will someday become 120 violins and violas.

Going to a wood dealer and picking up pieces of wood and looking at and tapping them is an easier way to find good wood, but working from the log can be done, and it is certainly grounding.

The Back Wood

Violins are typically made of European maple, which is similar to our soft or white maple. In this category we have mostly red maple, which has different characteristics depending on the soil it grows in, and we’ve also got Norway maple and silver maple. They have similar wood qualities and densities and can work well in violin making.

This maple gives the most characteristic violin sound, the sound most violinists are looking for, which is warmth with some pop. As you start moving away from that, you might get more warmth without the edge and without the cutting quality, or you might get brightness without the depth. So I make adjustments to accommodate, and hope the instrument will have a sound with a strong personality and a voice that will fit someone well.

Over the years, I have experimented with many types of wood. There have been some nice surprises along the way. In the early 1980s, as I was just getting started making violins regularly, a Quaker friend in Maine gave me a stash of wood to work with. In the 1920s or 1930s, Louie’s father had cut this wood for a local violin maker, and some was still in the loft of his garage. My friend was cleaning things out and asked if I wanted it. So that gave me a stash of New England wood to work with, mostly maple.

But there was a piece of wood in there that I could not identify. I concluded that it was cherry, but it was not cherry-colored; it was quite white. Cherry trees don’t usually have that much sap wood, but going by the smell, and the way the wood cut, and the way the tools worked with it, I believe it was cherry. Instruments made from cherry have a warmth to the sound, and a fair amount of edge. But it’s an edge with some cushion to it, as opposed to a bright, crisp edge. And that turned out to be a great-sounding instrument.

The Top

Violin tops are typically made of spruce, and I do usually use spruce for my instruments. There are a lot of different kinds of spruces. I regularly use two different types: New England spruce, which is reedier and harder, and Englemann spruce, which is lighter and softer, not as stiff as the New England spruce or European spruce.

The harder New England spruce gives brightness and power, and the Englemann gives more softness and flexibility in the way the instrument responds. But then these characteristics can all be compensated for in the way the instrument is made.

I have experimented with other top woods as well. I’ve used white cedar and red cedar, as well as Port Orford cedar, which is very closely related to European cypress, but it doesn’t have quite enough spring in it or the right kind of stiffness. I’ve not used any Italian cypress, but that is an intriguing thought.

I’ve also just made my first instrument with some very nice close-grained white pine. I have some white pine sitting out in the barn that was probably cut in the early 1800s. It’s a 12 inch wide shelf, exactly quarter cut all the way, that came out of an antique cupboard.

I did an experiment for the Oberlin Acoustics Workshop a few years back, where I produced five almost identical tops for one instrument so that they could be compared. The five included two tops each of red spruce and two of Englemann, identical except that within each pair, one was ammonia treated and one was not; and one top of Sitka spruce, which was harder than the New England spruce.

The experiment took place over a week. At the end of each day, I took the top off and put a new top on the instrument, and then set it up in the morning. It was then played for everyone so they could hear, and people were invited to come and test the instrument any way they wanted, using acoustic recording and various analyses.

The result was that the ammonia-treated tops were both preferable to the non-ammonia-treated tops, and I think the New England spruce was preferable to the Englemann and Sitka. But folks found it really hard to tell the difference. In preparing the tops for this experiment, rather than making all of the top to the same thicknesses, I tried to get them to respond the same. So if I were truly successful in that, they should be very similar, and it seemed they were.

Ultimately, it’s not just a question of the characteristic of the wood. If you work any suitable wood in a good way, it will end up having a good balance of characteristics. You can make a good instrument from just about anything, but each type of wood gives a voice that you can’t imitate; you can only influence it.

I’m happy for visitors to the shop to try out different instruments, so let me know if you’d like to come hear for yourself how instruments made from different wood compare.